Updated September 2017

In the 2017 edition of the Bank for International Settlements annual report, BIS outlines where the economy's Achilles heel lies - the accumulation of unprecedented levels of debt, a situation that could prove to be critical for several highly indebted nations as you will see in this posting. While the bank for central bankers notes that the global economy has strengthened over the past year with economic growth rates approaching long-term averages, there are four risks that could threaten the sustainability of the expansion:

In the 2017 edition of the Bank for International Settlements annual report, BIS outlines where the economy's Achilles heel lies - the accumulation of unprecedented levels of debt, a situation that could prove to be critical for several highly indebted nations as you will see in this posting. While the bank for central bankers notes that the global economy has strengthened over the past year with economic growth rates approaching long-term averages, there are four risks that could threaten the sustainability of the expansion:

1.)

a rise in inflation

2.)

financial stress as financial cycles mature

3.)

weakening consumption, demand and investment because of growing debt levels,

particularly at the household and corporate levels

4.)

a rise in protectionism

In

this posting, I want to focus on point three; the risks to the global economy

associated with what BIS terms "unusually high debt levels" and

"unusually limited room for policy manoeuvre(s)", that being the room

for central banks to raise interest rates.

Here

is a graphic showing how global debt as a percentage of GDP has risen since the

end of 2007 (i.e. the beginning of the Great Recession) for advanced economies

(AE) and emerging economies (EME) broken into general government debt in

yellow, non-financial corporate debt in blue and household debt in red:

Here

is a graph showing how public and private non-financial corporate debt has

soared as interest rates have plummeted since 1986:

One

of the great dangers is the sharp increase in corporate debt among emerging

economies, particularly where that debt is accrued in foreign currencies, a

situation that leaves companies highly vulnerable to unfavourable changes in

exchange rates.

Here

is a tell-all quote from the report:

"As

markets have grown used to central banks' helping crutch, debt levels have

continued to rise globally and the valuation of a broad range of assets looks

rich and predicated on the continuation of very low interest rates and bond

yields".

One look no further than the highly overvalued real estate

of two major centres in Canada, Vancouver and Toronto, where a crack shack will

set you back over a million dollars, to see how central bank policies have

completely distorted at least one aspect of the consumer marketplace.

Next,

let's look at a graphic that shows us two measures which can be used as early

warning indicators of future financial overheating and banking sector distress

as follows:

1.)

Credit-to-GDP gap - the deviation of the private non-financial sector

credit-to-GDP ratio from its long term trend (i.e. how quickly debt has raced

ahead of the long-term trend in economic growth). A reading above 10 is

considered dangerous and readings between 2 and 10 are considered risky.

2.)

Debt service ratios (DSR) which are measured as the sector's principal and

interest payments in relation to income. Debt service ratios greater than

6 are considered dangerous and those between 4 and 6 are considered risky.

Now, let's look at which nations are in the debt trap danger zone, the key part of this posting. Here

is the graphic with danger zones highlighted in red, the risky zones

highlighted in beige and includes a column which shows which economies will be

in danger if interest rates rise by 250 basis points:

As

you can see, the credit-to-GDP gap has reached levels signifying higher banking

sector risks in Canada, Hong Kong, China and Thailand. As well, if

interest rates rise by 250 basis points, the rise in the debt service ratio

suggest that the domestic banking system in Canada, China and Hong Kong are

under threat.

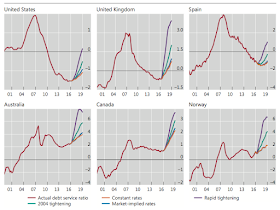

Let's

look at the several examples showing what household debt servicing burdens looks like under different interest rate

scenarios (in percentage points) for Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, Spain,

Australia and Norway:

It

is interesting to see that Canadian and United Kingdom households are highly vulnerable to

increases in debt servicing ratios when interest rates rise, yet not as bad as their peers in Australia and Norway, two nations famous for their highly overheated housing

market and growing household indebtedness. Fortunately for households in both the United States and Spain, significant debt deleveraging after the Great Recession makes them somewhat more immune to interest rate increases.

So, what does the central bank for central banks

think could happen when central banks begin to raise rates given the current debt inventory? Here's a

quote:

"Policy normalisation presents

unprecedented challenges, given the current high debt levels and unusual uncertainty.

A strategy of gradualism and

transparency has clear benefits but is no panacea, as it may also encourage

further risk-taking and slow down the build-up of policymakers’ room for

manoeuvre." (my bold)

In other words, central banks are damned if they

raise interest rates and damned if they don't, largely because

their policies have resulted in both risk-taking (i.e. the creation

of asset bubbles in stocks, bonds and real estate) and excess levels of debt. Gradually raising interest rates could well prove to be no solution to the problem of asset bubbles and debt accumulation since a rate increase of 25 basis points here and there is relatively meaningless, particularly when compared to the interest rate increases of past economic cycles.

Here's a summary from the report which

succinctly explains the potential debt crisis and how the world's central banks

have painted themselves into a "monetary policy corner":

"Otherwise, over long horizons, failing to

constrain financial booms but easing aggressively and persistently during busts

could lead to successive episodes of serious financial stress, a

progressive loss of policy ammunition and a debt trap. Along this path, for

instance, interest rates would decline and debt continue to increase, eventually

making it hard to raise interest rates without damaging the economy. From this perspective, there are some uncomfortable signs: monetary

policy has been hitting its limits; fiscal positions in a number of

economies look unsustainable, especially if one considers the burden of

ageing populations; and global debt-to- GDP ratios have kept

rising." (my bold)

The Federal Reserve and the world's other most

influential central banks have borrowed from the future. The long period

of near-zero interest rates will prove, in the long run, to be extremely

dangerous to the global economy, and could end up causing more economic pain

than the Great Recession, largely because of the central bank fuelled

"debt trap" that has been created since 2008.

With the markets sporting a glow from all-time record highs that are being made week after week it might be a good time to revisit the concept of irrational exuberance. We must consider the possibility we may be nearing the end of a 37-year run that will completely upend everything most people have come to believe about the economy. Since 2008 all growth has been built on a mountain of debt.

ReplyDeleteThose of us who have doubted and repeatedly predicted the collapse of this so-called recovery remain wrong because we have underestimated both the breadth and size of the global intervention of central banks and governments. Nobody in their right mind would have ever anticipated the sheer magnitude and scope of what has become a worldwide phenomenon. The article below questions when the burden of global debt will cause Atlas to shrug.

http://brucewilds.blogspot.com/2017/03/when-will-atlas-shrug-burden-of-global.html