Since the COVID-19 pandemic took ahold of the world and gave it a "good shake", the World Economic Forum and its oligarchist membership and leadership has taken a front row seat at the rebuilding of our society to "build it back better". One of the focuses of the group and, in particular, its leader and founder Klaus Schwab, is the intersection of humanity and technology. In Part 1 of this two part series, I looked at some quotes from Schwab's writings regarding "transhumanism", the future of humanity through the implementation of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. In Part 2, we will look at a concept that few of us are aware of, the Internet of Bodies or IoB, the ultimate goal of this group of self-appointed overlords.

We have all heard of the Internet of Things or IoT which refers to the billions of physical devices around he world that are connected to the internet, collecting and sharing data which allows us to control devices without being physically present. At the household level, these so-called smart devices include speakers, locks, lightbulbs, refrigerators, ranges and thermostats; basically objects which have the ability to communicate with or be controlled by a connection to the internet. In 2019, IDC estimated that there would be 41.6 billion connected IoT devices by 2025, generating 79.4 zettabytes of data (a zettabyte is one sextillion bytes)

As I noted above, the subject of this posting is the Internet of Bodies or IoB, a concept that has not reached the public's consciousness. According to RAND, the Internet of Bodies is described as follows:

"Within the broader Internet of Things (IoT) lies a growing industry of devices that monitor the human body and transmit the data collected via the internet. This development, which some have called the Internet of Bodies (IoB), includes an expanding array of devices that combine software, hardware, and communication capabilities to track personal health data, provide vital medical treatment, or enhance bodily comfort, function, health, or well-being."

In August 2020, the following article appeared on the WEF's website:

The author of the article is Xiao Liu, Fellow at the Centre for the Fourth Industrial Revolution at the World Economic Forum and an Assistant Professor in the Department of East Asian Studies at McGill University in Montreal, Canada as shown here:

You will observe that her areas of research are Chinese film and media and that she has no expertise in biomedical technology whatsoever.

Xiao Liu notes the following:

1.) We’re entering the era of the “Internet of Bodies”: collecting our physical data via a range of devices that can be implanted, swallowed or worn.

2.) The result is a huge amount of health-related data that could improve human wellbeing around the world, and prove crucial in fighting the COVID-19 pandemic.

3.) But a number of risks and challenges must be addressed to realize the potential of this technology, from privacy issues to practical hurdles.

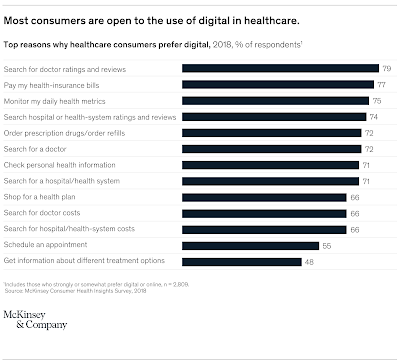

The article includes this graphic which shows that consumers are open to the use of digital in healthcare from McKinsey & Company:

While this may be the case for some aspects of healthcare, you will notice that NONE of the reasons why consumers prefer a digital aspect to their healthcare include anything about implanting or swallowing a device.

With this as a brief introduction to the WEF's views on the IoB, let's look at a recent document outlining the World Economic Forum's views on the IoB. In August 2020, the WEF released a Briefing Paper in collaboration with McGill University entitled "Shaping the Future of the Internet of Bodies: New challenges of technology governance" as shown here:

Here is the opening page of Chapter 1, informing us that "we have arrived":

Here is a diagram from the Briefing Paper showing examples of IoB technologies:

Here is a list of IoB technologies from the Briefing Paper:

"Generally, IoB technologies include medical devices, a variety of lifestyle and fitness tracking devices, other smart consumer devices that stay in proximity to the human body and an expanding range of body- attached or embedded devices that are deployed in enterprise, educational and recreational scenarios. It is worth noting that the IoB technologies examined here are mostly “personal devices”, in the sense that the devices always develop a relatively stable relationship with the individual body of the user over a regular, extended period of contact. This, therefore, excludes the type of biometric technologies that are installed in public and private spaces, such as facial recognition systems, fingerprint sensors and retinal scanners, which focus on collecting and processing the data of a large population or group rather than particular individuals....

IoB technologies can be characterized as non-invasive or less-invasive, in the sense that they are not expected to interfere with the structure or any function of the body; or as invasive, with sensors going under the skin to be implanted into or become part of the body.

Invasive technologies include, for example, digital pills – a recent drug-device combination developed to deliver encapsulated medicine and monitor medication adherence – which rely on ingestible mini-sensors to be activated in the patient’s stomach, and which then transmit data to sensors, the patient’s smartphone and other data portals. Other examples of smart medical implantables include: an internet-connected artificial pancreas as an automated insulin delivery system for diabetes patients; and robotic limbs for movement rehabilitation in people with physical mobility limitations. In recent years, increasing numbers of people have chosen to implant chips under their skin, not for medical purposes but as a personal choice to speed up their daily routines and for convenience – accessing their homes, offices or other devices just by swiping their hands, for example. As part of biohacking culture, people have also sought to enhance their bodies with implanted technology, from magnets and RFID chip implants to miniature hard drives and wireless routers.

Of course, the authors of the study note that there are social benefits to the IoB technologies:

1.) enable remote patient tracking and reducing cross infection

2.) improving patient engagement and promoting a healthy lifestyle

3.) advancing preventative care and precision medicine

4.) enhancing workplace safety

But, as is the case with everything that is too good to be true, there are risks associated with the IoB technologies:

1.) interoperability between systems from different manufacturers and data accuracy

2.) cybersecurity and privacy

3.) risks of discrimination and fairness in data analytics

Let's focus on two of these risks from the viewpoint of the WEF:

1.) cybersecurity and privacy:

"There is increasing awareness of the vulnerability of wearables and medical IoT devices to hacking and cyberattacks, which expose human lives to potential physical harm and privacy risks. Globally, healthcare cybersecurity breaches in 2018 accounted for 25% of 750 reported incidents, more than any other industry.19 The issue is no less grave for consumer devices. Researchers have found serious security flaws with children’s smartwatches, which hackers can use to track children, gain access to audio, and make phone calls to them.

Privacy is one major factor affecting consumers’ trust and adoption of IoB devices. Increasing adoption of IoB devices beyond traditional medical facilities also raises new concerns about security and privacy, while technical standards and policies are yet to reflect these new challenges. For example, an interactive map showing the whereabouts of people who use wearable fitness devices revealed information about the locations and activities of soldiers at US military bases. Taken as an aggregate, this is highly sensitive information because it describes military movements even though personal identifier information is removed from the published data. At a consumer level, geolocation data derived from a wearable can point to commuting patterns or other information that could be misused in the wrong hands. Amid the global outbreak of COVID-19, with the enlisting of data for coronavirus tracking and the relaxation of enforcement regarding health data in the US and other countries, the privacy of health data has generated serious concerns. The (im)balance between data privacy and the transparency required to tackle a public health emergency continues to be a contentious topic. For example, the use of smart thermometer data for health surveillance and to create a “US health weather map” has raised alarming privacy concerns. Some thermometer companies are using this personal information to market and sell the data to third-party companies."

2.) risk of discrimination:

"The use of IoB data with minute details of individual health conditions and life habits in insurance could fragment the solidarity foundation of insurance and shake its socioeconomic and ethical basics. Some insurers have already dug into vast amounts of personal data, ranging from home addresses and ownership, and education levels, to lifestyle data such as dietary habits, daily activities and exercises. The information is fed into computer algorithms to assign each individual a risk score for decisions regarding healthcare insurance, but also in other types of insurance, such as life insurance, disability insurance and even in areas not directly related to health, such as financial loans. The data from IoB technologies often includes fine-grained details of personal life as well as physical and mental health. The misuse of this data could lead to discriminative insurance policies and prices, making it harder for marginalized populations to access basic healthcare, and other types of insurance…

The increased risks of privacy intrusion and unfairness have already generated opposition from employees, unions and activists. In 2018, West Virginia teachers went on strike to demand the removal of a workplace wellness programme that was criticized for penalizing members for not scoring “acceptable” levels on biometric measures. Workers at UPS, McDonald’s and Amazon warehouses have also protested against the exacerbated work stress and precarity imposed by management through intensive data- collecting trackers, and requested new rules regarding employers who use tracking data to discipline employees."

I believe that is enough to digest for one posting. According to the World Economic Forum, the Internet of Bodies is already in place and is set to grow; unfortunately, we have become unwilling and unwitting peons in a game that will benefit the ruling class at the expense of our privacy and our personal information, all in the name of data harvesting and the ability to track our every move. While some of this technology may benefit humanity, to me, the risks associated with the growth of the Internet of Bodies far outweighs the benefits, particularly since we have to trust Big Pharma, Big Tech and Big Government with the most personal details about our lives. As this two part series has shown us, our overlords as represented by the World Economic Forum have very, very strong beliefs in the increasing implementation of a transhuman future; one where technology is merged with humanity with the ultimate goal of creating a better future, particularly in the post-COVID-19 era. To close, one aspect of a late-1980s and early-1990s classic television show comes to mind:

Very frightening

ReplyDelete(like google!!!)