Aside from setting

monetary policies, the Federal Reserve, through its regional banks, also provides

some very interesting research. In some cases, this research actually

shows how the Fed's policies have been relatively ineffective at curing the

problems that have appeared in the American economy since the beginning of the

Great Recession. This article by two researchers at the Federal

Reserve Bank of St. Louis explains quite clearly how the Fed has failed

America's long-term unemployed.

Here is a graph showing

both the unemployment rate (in orange) and the median number of weeks in

unemployment (in black) going back to 1970:

While the headline

unemployment rate has fallen and even though we are more than 6 years into the

post-Great Recession recovery, the median duration of unemployment for American

workers is still at the highest level since the early 1980s. The median

duration rose to as much as 25 weeks in 2010, more than twice the highest level

over the last 45 years and has since fallen to 12 weeks.

As we all know, by definition, workers

are considered to be long-term unemployed when they are unemployed for 27 weeks

or longer. As shown on this graph, the number of long-term unemployed

workers is still higher than it was prior to the Great Recession:

Let's look at a breakdown of these long-term unemployed workers and how the situation has changed for various age cohorts. From the research by

Alexander Monge-Naranjo and Faisal Sohail, it appears that long-term

unemployment (LTU) has impacted Americans far differently when age is taken into consideration. The authors found that LTU is concentrated in two main groups:

1.) those who are about

50 years of age

2.) those who are about

23 years of age

They note that the average of a worker

in LTU rose from 38.3 years in 2006 - 2007 to 40.1 years 2012 - 2013.

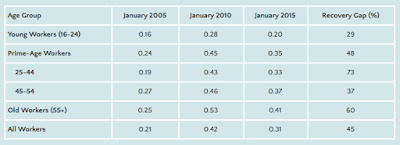

The authors divided the

long-term unemployed onto one of four age-based cohorts; ages 16 to 24, 25 to

44, 45 to 54 and 55 plus. Here is a table showing how the likelihood of entering long-term unemployed over time varied for each age cohort:

As you can see, the

likelihood of entering LTU prior to the Great Recession increased with age from

16 percent for the youngest workers to 27 and 25 percent for the oldest

workers. By January 2010, the likelihood of entering LTU rose to between

28 percent for the youngest workers to a high of 53 percent for workers aged 55

and older. By January 2015, the likelihood of being long-term unemployed

had dropped to between 20 percent for the youngest workers to a high of 41

percent for workers 55 and older. While that seems like a reasonable

recovery, in fact, it isn't that great since none of the age cohorts have

reverted to their January 2005 levels. As you can see from the last

column on the table, there is a very significant "recovery gap"

between the share of long-term unemployed for each age cohort from prior to the

Great Recession. For older workers, aged 55 and older, the share of

long-term unemployed is 60 percent higher than before the Great Recession and

for prime-age workers between the ages of 25 and 44, the share of long-term

unemployed workers is 73 percent higher than before the Great Recession.

This graph shows how the

age distribution of long-term unemployed workers has shifted from 2006 - 2007

to 2012 - 2013:

As the research shows,

long-term unemployed workers are getting older.

This research on the

changing pattern of long-term unemployment leads us to two possible conclusions based on the higher likelihood of being long-term unemployed for certain age groups:

1.) Prime-age workers who

were driven into long-term unemployment during the Great Recession are likely

to suffer permanent negative impacts on the remainder of their working careers.

2.) Older workers who

were driven into long-term unemployment during the Great Recession will find it

far more difficult to regain employment in their chosen profession because they

may not have the skills currently in demand by employers. This will lead

to postponed retirements.

The Fed's own research is

showing that their "heroic" monetary policies since 2008 have still left

millions of long-term unemployed Americans far worse off than they were prior

to the Great Recession. The impact of long-term unemployment has affected

both older and prime-age workers between the ages of 25 and 44 more than their

younger counterparts, a feature of today's job market that will be felt by

these workers for years to come.

Older workers who were driven into long-term unemployment during the Great Recession will find it far more difficult to regain employment in their chosen profession because they may not have the skills currently in demand by employers.

ReplyDeleteit seems the "skill" employers look for is the ability to work for a pittance

employers love fresh meat - can pay them less, more gullible etc etc