Now that the United States has abandoned its 20 year-long nation building experiment in Afghanistan, the most recent report from the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan (SIGAR) entitled "What We Need to Learn - Lessons From Twenty Years of Afghanistan Reconstruction" seems particularly pertinent:

This is the eleventh "Lessons Learned" report issued by the SIGAR since the Lessons Learned Project was implemented in late 2014. This report examines the past two decades of reconstruction effort, clearly outlining how Washington struggled to achieve its goals in education, health, rule of law, women's rights, infrastructure and security assistance.

Let's start with this quote from the report's Executive Summary:

"The U.S. government has now spent 20 years and $145 billion trying to rebuild Afghanistan, its security forces, civilian government institutions, economy, and civil society. The Department of Defense (DOD) has also spent $837 billion on warfighting, during which 2,443 American troops and 1,144 allied troops have been killed and 20,666 U.S. troops injured. Afghans, meanwhile, have faced an even greater toll. At least 66,000 Afghan troops have been killed. More than 48,000 Afghan civilians have been killed, and at least 75,000 have been injured since 2001—both likely significant underestimations.

The extraordinary costs were meant to serve a purpose—though the definition of that purpose evolved over time. At various points, the U.S. government hoped to eliminate al-Qaeda, decimate the Taliban movement that hosted it, deny all terrorist groups a safe haven in Afghanistan, build Afghan security forces so they could deny terrorists a safe haven in the future, and help the civilian government become legitimate and capable enough to win the trust of Afghans. Each goal, once accomplished, was thought to move the U.S. government one step closer to being able to depart.

While there have been several areas of improvement—most notably in the areas of health care, maternal health, and education—progress has been elusive and the prospects for sustaining this progress are dubious. The U.S. government has been often overwhelmed by the magnitude of rebuilding a country that, at the time of the U.S. invasion, had already seen two decades of Soviet occupation, civil war, and Taliban brutality."

When the United States undertook its nation-building exercise in Afghanistan, the nation had the following issues:

"Afghans had no experience participating in elections, much less administering them. There was no independent media, and civil society was anemic. Life expectancy was 56 years, lower than 83 percent of countries at the time. The mortality rate for children under the age of five was in the bottom 15 percent of countries globally. Women and girls were officially banned from schools and the workforce. Only 21 percent of eligible children were enrolled in primary school. Even as late as 2005, 64 percent of Afghan men and boys were illiterate, as were 82 percent of Afghan women and girls."

To assist Afghanistan, the United States government spent billions of dollars running programs with the following rather heady goals:

1.) Train, equip, and pay the salaries for hundreds of thousands of Afghan soldiers and police;

2.) Build a credible electoral process by funding elections, cultivating political parties, and training election officials and observers;

3.) Educate more Afghans, particularly girls and women, by building, repairing, staffing, and equipping schools;

4.) Reintegrate back into society tens of thousands of armed fighters with few other skills, an abundance of weapons, and ample opportunity to resume violence;

5.) Develop the private sector by training entrepreneurs, lowering the costs of starting and running businesses, and creating an environment that would attract foreign and domestic businesses to operate in Afghanistan;

6.) Reduce rampant corruption in the Afghan government to improve its performance and legitimacy;

7.) Reduce the cultivation and trade of poppy and provide alternative livelihoods for Afghan farmers;

8.) Deliver services at the local level so that Afghans in contested territory would come to favor the Afghan government over the Taliban;

9.) Improve the quality and accessibility of health care by building, repairing, staffing, and equipping medical facilities;

10.) Train and empower Afghan officials to sustain the above efforts after the United States departs by collecting their own revenue and effectively managing their own national budget.

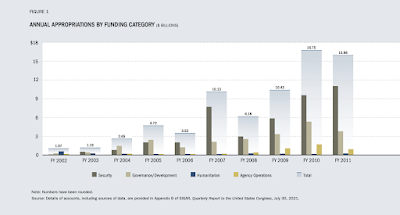

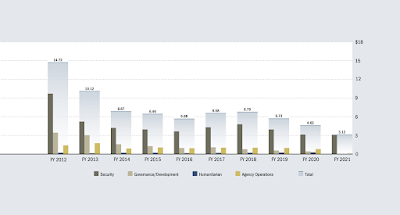

Here's what was spent on each funding category between fiscal 2002 and fiscal 2021:

SIGAR notes that some progress was made as follows:

1.) life expectancy had jumped from 56 years in 2001 to 65 years in 2018

2.) the mortality rate of children under 5 years of age dropped by more than 50 percent

3.) between 2002 and 2009, Afghanistan's per capita GDP nearly doubled and overall GDP nearly tripled even when accounting for inflation, however, the nation's per capita GDP moved from the world's fourth worst to the world's eighth worst.

4.) literacy among 15 to 24 year old males increased by 28 percentage points and 19 percentage points for females between 2005 and 2017.

After more than 760 interviews and reviewing thousands of government documents, SIGAR found that there are seven key lessons that Washington needs to learn before it exports its nation-building "skills" to other conflict zones around the world:

1.) Washington failed to develop a coherent strategy for what it hoped to achieve in Afghanistan - no single agency had the mindset, resources and expertise needed to develop, maintain and manage the efforts to rebuild Afghanistan. The initial goal of defeating al-Qaeda morphed into the goal of defeating the Taliban which morphed into ridding the nation of corrupt officials who were undermining the American rebuilding efforts. Here is a graphic showing the growth in the number of enemy-initiated attacks over the period from 2002 to 2020:

2.) Washington failed to understand how long the mission would take - Washington consistently underestimated the amount of time needed to rebuild Afghanistan and the choices made resulted in corruption with American funds ending up in the hands of Afghani powerbrokers.

3.) Washington failed to ensure that the projects were sustainable over the long-term - reconstruction efforts should serve as a foundation for building governments, civil society and commerce indefinitely, however, Washington's efforts were not sustainable over the long-term with billions of tax dollars being wasted as projects were either not used or fell into disrepair. As well, Afghani nationals and institutions did not have the capacity to take responsibility for managing the projects.

4.) Washington failed to staff the mission with trained professionals - this was considered by SIGAR to be one of the greatest failures of the mission for both civilian and military personnel. For example, DoD police advisors watched American television shows to learned about policing and civil affairs teams were created using PowerPoint presentations. Continuous staff rotations also impeded progress as projects were restarted from scratch and new staff did not learn from the mistakes made by their predecessors.

5.) Washington failed to account for the challenges that were posed by national insecurity - the absence of violence was a precondition for Washington's plans for Afghanistan. For example, attempts to set up a viable electoral system was made difficult as insecurity spread across the nation, resulting in voters who were intimidated and polling stations that were closed on election days. American officials were unable to convince rural Afghanis who lived in Taliban-contested areas that there was a benefit to supporting a democratically elected government.

6.) Washington failed to tailor the reconstruction efforts to the Afghani context - a detailed understanding of Afghanistan's social economic and political dynamics was needed to ensure that reconstruction efforts would succeed. These three dynamics were never understood by U.S. officials who forced Western technocratic models onto Afghan economic institutions, trained local security forces in weapons that they neither understood nor maintain, imposed formal laws on a nation which has traditionally addressed disputes through informal means and struggled to understand the cultural and social barriers that existed for girls and women.

7.) Washington failed to monitor and evaluate the impact of programs - Washington and its representatives in Afghanistan were never able to determine which programs worked and which programs did not. This was particularly the case in Afghanistan because the environment was complex and unpredictable. As well, staff turnover was rapid and multiple agencies were needed to coordinate programs, sacristy and access restrictions. Here is a quote:

"The absence of periodic reality checks created the risk of doing the wrong thing perfectly: A project that completed required tasks would be considered “successful,” whether or not it had achieved or contributed to broader, more important goals."

Let's look at the conclusions of the report:

"This report raises critical questions about the U.S. government’s ability to carry out reconstruction efforts on the scale seen in Afghanistan. As an inspector general’s office charged with overseeing reconstruction spending in Afghanistan, SIGAR’s approach has generally been technical; we identify specific problems and offer specific solutions. However, after 13 years of oversight, the cumulative list of systemic challenges SIGAR and other oversight bodies have identified is staggering. As former National Security Advisor Stephen Hadley told SIGAR, “We just don’t have a post-conflict stabilization model that works. Every time we have one of these things, it is a pick-up game. I don’t have confidence that if we did it again, we would do any better.”

As this report shows, there are multiple reasons to develop these capabilities and prepare for reconstruction missions in conflict-affected countries:

1.) They are very expensive. For example, all war-related costs for U.S. efforts in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Pakistan over the last two decades are estimated to be $6.4 trillion.

2.) They usually go poorly.

3.) Widespread recognition that they go poorly has not prevented U.S. officials from pursuing them.

4.) Rebuilding countries mired in conflict is actually a continuous U.S. government endeavor, reflected by efforts in the Balkans and Haiti and smaller efforts currently underway in Mali, Burkina Faso, Somalia, Yemen, Ukraine, and elsewhere.

5.) Large reconstruction campaigns usually start small, so it would not be hard for the U.S. government to slip down this slope again somewhere else and for the outcome to be similar to that of Afghanistan.

Maybe, just maybe, American taxpayers would be best served if Washington learned its lesson and stayed out of the nation rebuilding business although that is highly doubtful.

Nation building? That's rich. Do you know that a rat, when electrocuted, can restart his own heart. These people are cunning combinations of rat and ape but grifting murderers are going to grift and kill. They spend decades using a local populace as target practice for their new expensive weapons systems while telling citizens to worry about Cuba. US is the sickest, most terroristic, genocidal country in the history of the world, just going in numbers of millions killed.

ReplyDeleteI probably should have put "nation rebuilding" in quotes as what Washington does in other nations is far from "building" anything.

ReplyDelete