Updated February 12, 2015

Switzerland National Bank's (SNB) recent announcement that they were allowing the value of the Swiss franc to float upwards against the euro, discontinuing the ceiling exchange rate of CHF1.20 to one euro and that they were cutting interest rates on deposits to minus 0.75 percent took the market by surprise. Up until January 15, 2015, the Swiss central bank sold Swiss francs whenever the franc threatened to rise above the 1.20 per euro mark. This is the second time in recent months that Switzerland has taken steps to prevent a overvaluation of the Swiss franc; on December 18, 2014, the SNB announced that it was allowing interest rates on sight deposit accounts to fall into negative territory at minus -0.25 percent. Why is the Swiss National Bank doing this and what do negative interest rates mean?

Switzerland National Bank's (SNB) recent announcement that they were allowing the value of the Swiss franc to float upwards against the euro, discontinuing the ceiling exchange rate of CHF1.20 to one euro and that they were cutting interest rates on deposits to minus 0.75 percent took the market by surprise. Up until January 15, 2015, the Swiss central bank sold Swiss francs whenever the franc threatened to rise above the 1.20 per euro mark. This is the second time in recent months that Switzerland has taken steps to prevent a overvaluation of the Swiss franc; on December 18, 2014, the SNB announced that it was allowing interest rates on sight deposit accounts to fall into negative territory at minus -0.25 percent. Why is the Swiss National Bank doing this and what do negative interest rates mean?

Keeping in mind that it

is generally a nation's commercial banking system that has money on deposit

with a central bank, the theory behind negative interest rates is that by

charging commercial banks for holding money with the central bank, the banking

system is forced to seek better returns elsewhere through one of two

mechanisms:

1.) investing in the

domestic economy through lending to businesses and individuals within the

Eurozone. This will help drive up economic growth in the local economy.

2.) transferring their

money to foreign central banks or banking systems. As capital flows out

of a nation, it helps weaken its currency and makes the nation's exports more

competitive since the price drops because of the lower exchange rate.

This also drives up economic growth.

Basically, the SNB is lowering interest rates to ensure that monetary conditions do not tighten, a problem that could occur when the Swiss franc appreciates as investors increased their demands for a safe haven investment vehicle. Introducing negative interest rates make it less attractive for investors to hold Swiss franc assets and investments.

Economists believed that

negative interest rates were a sure-fire way to stimulate an economy, however,

the example of Europe clearly shows otherwise. Back on June 11, 2014, the European Central Bank (ECB)

cut interest rates on its deposit facility to minus 0.1 percent. This

negative interest rate applied to:

1.) banks’ average

reserve holdings in excess of the minimum reserve requirements;

2.) government deposits

held with the Eurosystem that exceed certain thresholds that will be set in the

relevant Guideline to be published by 7 June;

3.) Eurosystem reserve

management services accounts if not currently remunerated;

4.) participants’ account

balances in TARGET2 (payment transaction settlements between banks and between banks and the ECB);

5.) non-Eurosystem NCB

balances (overnight deposits) held in TARGET2; and (vi) other accounts held by

third parties with Eurosystem central banks when stipulated that they are not

currently remunerated or are remunerated at the deposit facility rate.

On September 4, 2014, the ECB announced this:

“At today’s meeting the Governing Council of the ECB took the following

monetary policy decisions:

1 The interest rate on the main refinancing operations of the

Eurosystem will be decreased by 10 basis points to 0.05%, starting from

the operation to be settled on 10 September 2014.

2 The interest rate on the marginal lending facility will be

decreased by 10 basis points to 0.30%, with effect from 10 September 2014.

3

The interest rate on the

deposit facility will be decreased by 10 basis points to -0.20%, with

effect from 10 September 2014.

”

As an aside, in contrast to the ECB, the Federal Reserve actually pays interest on both required reserve balances (balances that are held to satisfy depository institutions' reserve requirements) and on excess reserves (balances held in excess of required reserve balances). The Federal Reserve has paid interest of 0.25 percent on these reserves since January 2009. This may not seem like much, however, it has led to a massive explosion in the size of excess reserves held by the Fed as shown here:

This is $2.5 trillion that commercial banks are NOT lending to consumers and businesses.

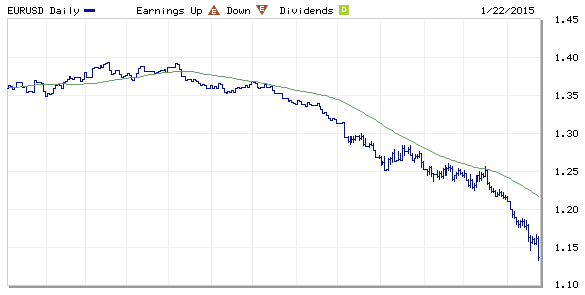

Now, back to Europe. Let's look at what happened to the euro to United States

dollar exchange rate over the last half of 2014 and the first weeks of 2015:

After the ECB cut

interest rates on deposits to negative territory, the euro dropped from USD1.36 to the euro to its current level of USD1.12, a drop of 17.6 percent.

This should have stimulated Europe's economy over the past quarter since

goods imported into Europe are more expensive for domestic consumers and goods

exported from Europe are less expensive for overseas consumers.

In fact, this is what has

happened to Europe's economy:

Quarter-over-quarter

growth in the third quarter of 2014 rose by a minuscule 0.2 percent, up from 0.1 percent in the second

quarter of 2014 for the euro area (EA18).

Here is what

quarter-over-quarter growth rates for each of the EU28 member states looked

like in the third quarter of 2014:

Now that's what we call

modest improvement in economic growth!

So what happened to all

of that money that banks were supposed to invest in loans to stimulate economic

growth? It appears that a substantial portion of that money went directly

into three places:

1.) Switzerland where the

euro dropped in value against the Swiss franc as shown here:

2.) Germany where the

money went into bunds, pushing the yield on five year bunds into negative

territory as shown here:

This tells us that

investors are desperately seeking to avoid the substantial capital losses that

can occur when investing in bonds that carry a higher degree of risk and that

they are perfectly willing to let Germany charge them to hold onto their money.

3.) United States where,

as I showed above, the value of the euro against the United States dollar has

dropped by 14.7 percent over the last six months. European purchases of Treasuries are still

taking place, particularly given that the interest rate paid on Treasuries

exceeds the rates on German and Swiss bonds. It is also quite likely that the current ultra-low rates on Treasuries are due to the inflow of money from Europe. As the value of the USD climbs, it will put significant pressure on the American trade balance as U.S. exports become more and more expensive and imports become cheaper. At some point, the Federal Reserve will have to act to push the value of the U.S. dollar down, perhaps following the lead of the SNB and ECB into negative interest rate territory.

As we can see from this

posting, negative interest rates are definitely not the panacea that will cure

Europe's economic woes. Obviously, the positive aspects of negative

interest rates in Europe have failed to appear, at least to this point in time. In fact, the very existence of

negative interest rates in the first place suggests that all of the monetary

policy experimentation by the world's central bankers has been an abject

failure. In their desperate efforts to revive the world's economy during

2008 and 2009, the efforts of central bankers have ended up painting them into a policy corner

from which extraction appears to becoming extremely complex and perhaps

impossible. The spillover effects from the past five years of central bank

intervention are becoming increasingly difficult to control and predict; the example of Switzerland is just the latest example of monetary policy failure.

No comments:

Post a Comment